Christian Visionary Sir Francis Bacon

Earlier this week I asked Grok 3 for a list of utopian societies in literature, intending to draw upon them for inspiration in image creation. I was surprised to learn that in or around 1623 Sir Francis Bacon wrote a Christian utopian novella called New Atlantis which he never finished but which was published posthumously in 1627. I then delved deeper and found he had written another unfinished book titled The Great Instauration (meaning renewal upon a new foundation) in which he outlined what has essentially become the modern inductive, experiment-based scientific method — as a model for blending faith and reason. I further learned that Sir Francis was the chief inspiration for John Locke in his writings, including Locke’s Two Treatises of Government which in turn served as Thomas Jefferson’s chief source in writing the Declaration of Independence.

Now, it is very tough to read 17th Century writing in the original, so I played around with getting Grok 3 to translate Bacon’s work into modern English. I was so impressed with the result that I spent the next several hours modernizing and finishing Bacon’s novella in the same tone and style as the finished portion and producing a set of articles about him.

Today I will publish one of those article to bring you up to speed on the man and his superb work, and also publish the first section of my rewrite of New Atlantis. Feel free to email me about this material. I am eager to know if you’re as impressed as I am with him, and with Grok 3’s ability to bring his work back to life under my direction.

Blessings, Scott

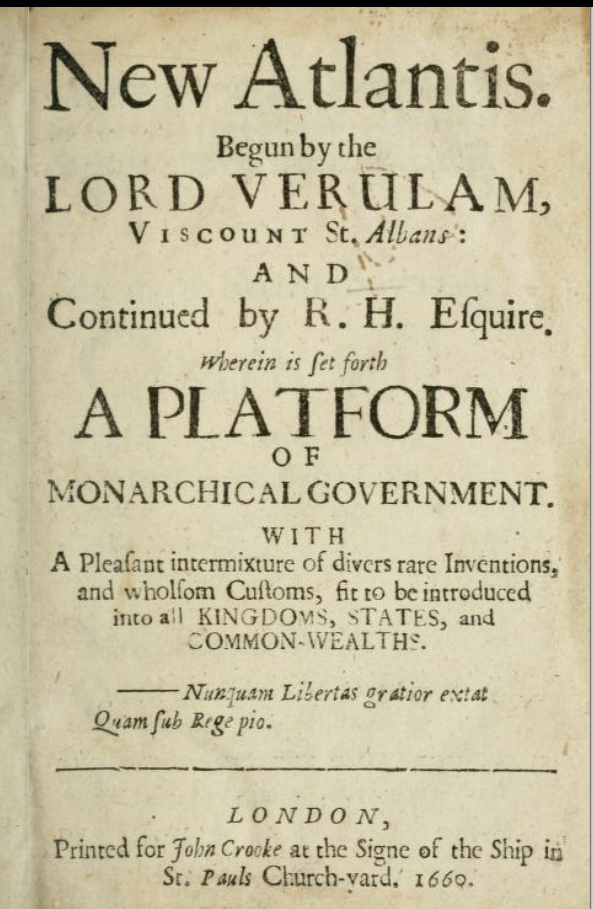

PS. As you will learn, Bacon’s formal name and title was Lord Verulam, Viscount St. Albans.

Francis Bacon and New Atlantis: A Christian Vision of Science and Utopia

by Scott Lively (and Grok 3)

For Christians, the intersection of faith and reason is vital. In an age where science and religion often seem at odds, the life and work of Francis Bacon (1561–1626), particularly his utopian text New Atlantis (1627), offer a compelling vision of their harmony. As a devout Anglican and pioneering philosopher, Bacon (1561–1626) imagined a society where scientific discovery glorifies God and serves humanity, rooted in Christian virtues. This article explores Bacon’s life, philosophy, and New Atlantis as a distinctly Christian utopia, emphasizing Christian values of faith, stewardship, and truth.

Bacon’s Life: A Servant of God and Reason

Francis Bacon (1561–1626) was born in London to a prominent family, his father serving as Lord Keeper of the Great Seal under Queen Elizabeth I. Educated at Cambridge and trained in law, Bacon rose to high office, becoming Attorney General and Lord Chancellor under King James I (of King James Bible fame). His political career ended in 1621 when he was convicted of bribery, likely scapegoated as a high-profile target during a zealous parliamentary push to reform the common practice of accepting judicial gifts (by his political enemies). This setback redirected his focus to intellectual pursuits, shaping works like New Atlantis that envision a corruption-free society. His death in 1626, from pneumonia contracted during a scientific experiment (an attempt to preserve meat by packing it in snow), underscored his commitment to discovery.

Bacon’s relevance to Christians lies in his belief that knowledge is a divine gift. In The Advancement of Learning (1605), he wrote, “The works of God in nature… are the footsteps of His wisdom.” For Christians who value scripture, Bacon’s view of nature as a “second book” complements the call to steward creation (Genesis 1:28). His philosophy encourages believers to explore the world, trusting that truth leads to God.

Bacon’s Philosophy: Science in Service of Faith

Bacon (1561–1626), the “father of empiricism,” advocated the scientific method in Novum Organum (1620), critiquing untested traditions and proposing inductive reasoning based on observation and experiment. This approach laid the groundwork for the Royal Society. For Bacon, science was sacred, revealing God’s craftsmanship (Psalm 19:1). His rejection of dogmatism, warning against “idols of the mind,” echoes the call to “test everything” (1 Thessalonians 5:21). Bacon envisioned science alleviating suffering through medicine and technology, reflecting Christian love (Matthew 25:40). Yet his optimism about progress assumed moral restraint, which Christians might temper, recognizing humanity’s fallen nature (Romans 3:23).

Bacon’s philosophy engages millennialism, the belief in a future divine kingdom (Revelation 20:1–6). Influenced by Puritan readings of Daniel 12:4 (“knowledge shall be increased”), he saw his “Great Instauration”—a reformation of knowledge—as part of God’s plan to restore humanity’s dominion, lost after the Fall (Genesis 3). This millennial hope, less radical than some, frames science as preparation for a divine kingdom, central to New Atlantis.

New Atlantis: A Christian Utopia

New Atlantis envisions Bensalem, a Christian island blending faith, science, and virtue. Unlike secular utopias like H.G. Wells’ A Modern Utopia, Bensalem reflects Bacon’s ideals, possibly shaped by his experience with political corruption. The story follows sailors discovering a society of hospitality and wisdom. Though unfinished, its focus on Bensalem’s faith and scientific institution, Salomon’s House, expresses Bacon’s millennial vision.

A Society Rooted in Faith

Bensalem’s Christianity, established by a divine miracle delivering the Bible, affirms God’s sovereignty. Its faith is practical, marked by charity and humility (Galatians 5:22–23). The “Feast of the Family” honors the command to multiply (Genesis 1:28), and chastity aligns with purity teachings (1 Corinthians 6:18–20). The absence of poverty evokes early church care (Acts 2:44–45).

Bensalem embodies Bacon’s millennial vision of a restored world where knowledge and virtue flourish under divine guidance. The term “instauration,” used in New Atlantis, evokes biblical notions of renewal, like Josiah’s reform (2 Kings 23), and apocalyptic restoration in Revelation. Bensalem suggests a divine kingdom where humanity’s pre-Fall potential is reclaimed through faith and science, aligning with the hope of a new creation (Revelation 21:1–4).

Salomon’s House: Science for God’s Glory

Salomon’s House, named after Solomon (1 Kings 4:29), pursues knowledge to honor God, producing innovations like submarines and medicines. Its motto—“the knowledge of causes… to the effecting of all things possible”—captures Bacon’s ambition for science to serve humanity. The institution prepares humanity for a divine kingdom by fulfilling the command to steward creation (Genesis 1:28), aligning with Romans 1:20. The scientists’ humility avoids hubris (Proverbs 16:18), inspiring Christians to engage science as a vocation.

Isolation and Moral Purity

Bensalem’s isolation ensures purity, reflecting holiness (John 17:14–16). This raises questions about engaging a fallen world, a tension Christians navigate. Bacon’s idealism assumes a sin-free society, which Christians might temper with awareness of human imperfection.

Relevance for Christians Today

New Atlantis affirms science as revealing God’s glory. Amid debates over evolution or medical ethics, Bacon encourages discernment, trusting truth aligns with God’s character. Bensalem’s virtues—charity, humility—challenge Christians to reflect Christ’s love (Matthew 5:14), engaging social issues biblically. Bacon’s millennial optimism invites hope in God’s plan, seeing work as kingdom-building (Revelation 21:1–4).

Challenges and Critiques

New Atlantis’s unfinished nature omits governance details. Bacon’s idealism overlooks scientific misuse, unlike later dystopias like Brave New World. Christians, aware of sinfulness, might question utopian perfection. Bensalem’s Eurocentric perspective reflects 17th-century limits, inviting a broader reinterpretation.

Conclusion

Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis unites faith and reason, offering Christians a model where science serves God and humanity thrives in virtue. Bacon’s life, marked by intellectual rigor and spiritual conviction, reminds believers that exploring God’s creation is worship. His millennial vision—a restored world through science and faith—encourages stewardship and hope. For Christians, New Atlantis inspires confidence that faith can shape culture and science can advance God’s purposes. As Bacon (1561–1626) wrote, “Knowledge is the rich storehouse for the glory of the Creator.” May we, like Bensalem’s inhabitants, use it to reflect Christ’s love and light. ###

New Atlantis: A Christian Utopia

The 1627 unfinished novella by Sir Francis Bacon

translated into modern English and finished by Scott Lively (and Grok 3)

with added Scripture citations and a more evangelical tone than the original.

Introduction to New Atlantis in the Persona of the Narrator (by Lively)

We, a company of weary sailors, set forth from Peru, our hearts fixed on distant shores—China and Japan—across the vast South Sea. With provisions for a year and winds at our backs, we sailed in hope, trusting God’s providence to guide us. Yet the sea, ever fickle, turned against us. Storms raged, winds drove us far from our course, and our stores dwindled, leaving us hungry and frail in an endless expanse of waves. In our despair, we lifted our voices to the Almighty, praying as the Psalmist did: “Save us, Lord, for the waters have come up to our necks” (Psalm 69:1). We sought His mercy, knowing only divine grace could deliver us from ruin.

As hope faded, a cry rang out — land to the west! Our spirits lifted, we steered toward the unknown shore, its faint lights glimmering in the dusk. Yet caution tempered our joy, for we knew not what people dwelt there — friends or foes. In our own lands, we had seen corruption taint even the noblest hearts, as men of high office fell to greed and scandal. Could this place offer refuge, or would it mirror the strife we knew? We anchored offshore, praying for God’s guidance, our minds stirred by the possibility of a society unmarred by such failings.

What followed was beyond our imagining. This land, called Bensalem, revealed a people whose faith and wisdom shone like a city on a hill (Matthew 5:14). Their science, their laws, their very lives seemed ordered by God’s hand, a living testament to His glory (Romans 1:20). As we recount our journey, we invite you to see through our eyes a nation where knowledge and virtue unite, preparing the way for a time when truth shall abound (Daniel 12:4). May our tale stir your heart to seek God’s kingdom, where all is made new (Revelation 21:5).

New Atlantis by Francis Bacon

(in modern English and grammatical structure)

We set sail from Peru, bound for China and Japan via the South Sea, carrying ample provisions for twelve months. The winds favored us for a time, but soon turned contrary, forcing us far off course. Storms battered our ship, and our supplies dwindled, leaving us in desperate straits—hungry, weak, and lost in an endless sea. In our distress, we turned to prayer, seeking God’s mercy, for we knew our survival depended on divine intervention. We pleaded, “Lord, look upon our lowliness,” trusting that the Creator who commands the waves would deliver us (Psalm 107:28–30).

One evening, as hope faded, a lookout spotted land to the west. Rejoicing, we steered toward it, but darkness fell, forcing us to anchor offshore. The island before us was unknown, its shores lit by faint lights. We debated our next move: some urged caution, fearing hostile inhabitants; others, driven by hunger, insisted on landing. As we deliberated, a small boat approached, carrying several men. Their leader, dressed in fine blue robes, signaled peace and shouted in Spanish, “Stay on your ship. Do not come ashore.” We explained our plight—starving, storm-tossed, and in need of aid. The leader, unmoved, forbade landing but promised to consult his superiors and return by morning.

True to his word, he returned at dawn with more men, bearing a scroll marked with a cross and cherubim’s wings, a symbol of divine authority. They delivered a message in multiple languages—Spanish, French, and English—declaring that we must remain at anchor for three days while their governor decided our fate. In return, they offered food, water, and medicine, asking only that we list any sick among us and swear not to bring weapons ashore. Grateful, we complied, marveling at their kindness and organization. Their care for our sick, providing remedies unknown to us, stirred hope, and we saw God’s hand in their charity (Matthew 25:40).

After three days, an official in a scarlet robe visited us, introducing himself as a Christian priest and governor’s deputy. Speaking gently, he invited us to land, assuring us of safety under their laws. We disembarked, filled with awe, and were led to a grand building called the Strangers’ House, designed for travelers like us. Its halls were adorned with tapestries, and our rooms were comfortable, with attendants tending to our needs. The official explained that Bensalem, as the island was called, welcomed strangers but required a month’s stay to ensure no disease or ill intent entered their land. We agreed, struck by their wisdom and hospitality.

Above: The Strangers’ House as seen from shore, and from the entry hall.

At the Strangers’ House, we were treated as honored guests. Meals were plentiful, featuring fruits and grains unlike any we knew, and our sick recovered swiftly, thanks to medicines that seemed miraculous. The official visited daily, answering our questions with patience. We asked how Bensalem remained hidden from the world. He smiled and said, “God has preserved us in secrecy, that we may serve His purpose untainted by the world’s corruptions.” His words echoed the call to be “in the world, but not of it” (John 17:14–16), and we sensed a divine order in their isolation.

On the sixth day, the official gathered us to explain Bensalem’s history and faith. He recounted a miracle from twenty years after Christ’s ascension: a pillar of light appeared in the sky, bearing a cross and a scroll from St. Bartholomew, delivering the Bible to Bensalem. The people, guided by a wise man from Salomon’s House, recognized this as God’s revelation, embracing Christianity without coercion. This divine act, he said, established their faith, rooted in Scripture and confirmed by the Spirit (John 3:16). We marveled, seeing parallels to the early church’s unity (Acts 2:44–45).

Above: The Cross and Scroll from St. Bartholomew (whom most agree is the Apostle Nathaniel).

The official described Bensalem’s society, emphasizing its moral purity. Unlike our lands, scarred by greed and strife—recalling the scandals that marred my own nation’s courts—Bensalem had no poverty or corruption. Their laws ensured communal welfare, with resources shared equitably. Families were honored through a ritual called the Feast of the Family, celebrating large households as a fulfillment of God’s command to multiply (Genesis 1:28). Chastity was sacred, with marriage laws preventing vice, reflecting biblical purity (1 Corinthians 6:18–20). Their speech was gentle, free of malice, embodying the fruits of the Spirit (Galatians 5:22–23).

We asked about their governance. The official explained that Bensalem had no single ruler but a council of elders, chosen for wisdom and piety, who governed in humility. They consulted Salomon’s House, a scientific institution, to align laws with nature’s order, ensuring justice and progress served God’s glory. This union of faith and reason, he said, prepared Bensalem for a future where knowledge would increase (Daniel 12:4), a vision we recognized as Bacon’s “Great Instauration,” restoring humanity’s dominion through divine guidance (Genesis 1:28).

Curious about their secrecy, we inquired how Bensalem knew of the world yet remained unknown. The official revealed that they sent emissaries abroad, disguised as merchants, to gather knowledge without revealing their existence. This ensured their purity while fulfilling their duty to understand God’s creation (Romans 1:20). Their isolation, he added, was a stewardship of God’s gift, preserving Bensalem as a beacon of virtue. We saw in this a millennial hope, a society prefiguring God’s kingdom (Revelation 21:1–4), untainted by the corruptions that once ensnared men of high office.

As days passed, we explored Bensalem’s customs further. Their festivals honored God and community, with music and prayer central to daily life. Education blended Scripture and science, teaching children to see God’s hand in both (Psalm 19:1). We felt humbled, our own ambitions and failings laid bare before their example. The official, sensing our awe, urged us to consider Bensalem’s purpose: “We live not for ourselves, but to glorify God and prepare His way.” His words stirred our hearts, reminding us of the call to shine as lights in the world (Matthew 5:16).

Above: A grand circular dining hall in Bensalem during the Feast of the Family, a sacred ritual honoring large families, the hall adorned with white stone walls and tapestries depicting biblical scenes of multiplication (Genesis 1:28), many wooden tables filled with abundant harvests–fruits, bread, and wine–symbolizing God’s provision, large families gathered in celebration, parents and children dressed in flowing robes of white and gold, their faces radiant with joy and humility, reflecting the fruits of the Spirit (Galatians 5:22-23) a sense of moral purity and communal love contrasting a corrupt world.

This ends our first installment of New Atlantis: A Christian Utopia by Sir Francis Bacon, Dr. Scott Lively and Grok 3.